FCC Commissioner Seeks Investigation of Wi-Fi Hotspot Limitations at Presidential Debate

At Monday’s presidential debate, host Hofstra University ruffled feathers by reportedly moving to prevent journalists, attempting to file stories from the scene, from relying on their own wireless hotspots to get online. The move was seen by some as an effort to force reporters to use the venue’s wireless service – said to cost $200 – and caught the attention of the FCC. Indeed, one Commissioner called for an investigation on Tuesday afternoon, although Hofstra’s practices may have differed, possibly materially, from those that have landed other venues in trouble with the Commission.

The FCC’s History on Wi-Fi Blocking

The FCC has long staunchly and actively opposed “Wi-Fi blocking,” which it describes as “intentionally block[ing] or disrupt[ing] personal Wi-Fi hot spots on [the] premises [of a commercial establishment], including as part of an effort to force consumers to purchase access to the property owner’s Wi-Fi network.” In 2014, the Commission reached a $600,000 settlement with Marriot over the practice; in 2015 Smart City Holdings agreed to pay $750,000 to settle similar allegations; and a few months later the Commission threatened M.C. Dean with a $718,000 fine for blocking Wi-Fi at the Baltimore Convention Center.

After hospitality industry groups petitioned the FCC, seeking clarity regarding what network management techniques would be allowed, the Commission posted an “enforcement advisory” on its website headed, “WARNING: Wi-Fi Blocking is Prohibited. Persons or Businesses Causing Intentional Interference to Wi-Fi Hot Spots Are Subject to Enforcement Action,” and promising to “aggressively investigat[e] and act[] against such unlawful intentional interference.” The same day that the enforcement advisory went up, Commissioner Jessica Rosenworcel, speaking at the 2015 “State of the Net Conference,” underscored the FCC position, saying, “Let’s make clear that we will not tolerate malicious or willful interference with Wi-Fi.”

A Commissioner Reacts

A Commissioner Reacts

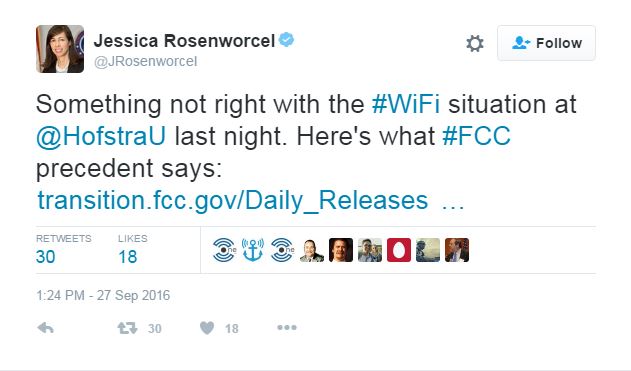

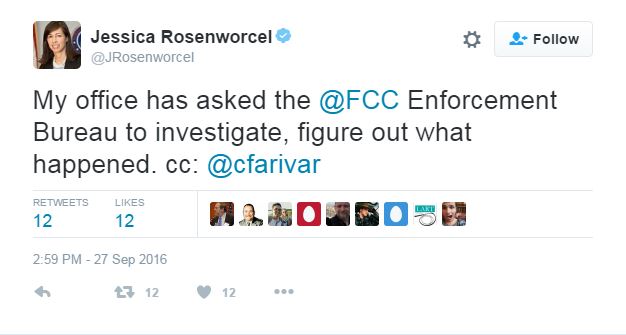

News of Hofstra’s reported attempts to restrict journalists’ Wi-Fi options at Monday’s debate reached Commissioner Rosenworcel quickly. Early Tuesday afternoon, she said via Twitter that “something is not right” with the goings on at Hofstra, and tweeted out a link to the FCC’s Consent Decree with Smart City Holdings. About an hour and a half later, she tweeted, “My office has asked the @FCC Enforcement Bureau to investigate, figure out what happened.”

Service (and Other) Concerns

Service (and Other) Concerns

A few hours after Commissioner Rosenworcel advised the twitterverse that the Enforcement Bureau had been contacted, journalist Cyrus Farivar, who writes for the technology publication Ars Technica, tweeted a brief statement he had received from Hofstra. That statement emphasizes the service issues that a roomful of individual Wi-Fi hotspots can pose: “For Wi-Fi to perform optimally the system must be tuned with each access point and antenna. When other Wi-Fi access points are placed within the environment the result is poorer service for all.” Concerns about the impact of the FCC’s enforcement position on a venue’s ability to provide adequate service while maintaining cybersecurity are real, and have been the subject of comments by me and others. As Dian Barber noted in Facility Manager Magazine last year:

Tasked by clients with providing robust connectivity and restricted from interfering with these “hotspot” devices by Section 333 of the Communications Act and a 2015 FCC Enforcement Advisory, venues face huge issues of interference, integrity, security, compromise of mission-critical services and “noise” disruption while still being expected to provide an exceptional quality of service.

Needless to say, it is a difficult needle that Hofstra needed to thread during what has been called the most-watched presidential debate in history.

Legal and Factual Questions

Commissioner Rosenworcel’s concern is that the Wi-Fi blocking activity violates Section 333 of the Communications Act, which provides, “No person shall willfully or maliciously interfere with or cause interference to any radio communications of any station licensed or authorized by or under this chapter or operated by the United States Government.” 47 U.S.C. § 333. This position is not entirely uncontroversial within the Commission – Commissioners Ajit Pai and Michael O’Rielly both dissented in the M.C. Dean action – and has yet to be tested by a court.

The precise details of what went on at Hofstra remain somewhat murky, but reports suggest that – unlike in the Marriot, Smart City, and M.C. Dean cases – no automatic interference techniques were utilized at the debate. Rather, according to some, technicians patrolled the press room using Wi-Fi hotspot detection devices, and asked hotspot-using journalists to turn them off or have their credentials revoked. One outlet reported hearing from the FCC that “Preliminary reports suggest that Hofstra was acting on an agreement with media guests to not use personal Wi-Fi hotspots while on the university’s premises,” which “is different from active Wi-Fi blocking, or deauthentication, which the FCC’s Enforcement Bureau found to be occurring in prior enforcement actions.”

If correct, these factors may distinguish the Hofstra scenario from the prior FCC enforcement actions, sufficiently to avoid an enforcement proceeding. Nonetheless, this is a developing area, in which policy is arguably written one enforcement action at a time, so the expected FCC investigation will be one to watch.